Contingencies in Sustainabilitism

Devin Halladay

This essay is a reflection on the contingencies we must acknowledge and address as designers (and artists, engineers, accountants, whatever you are). I will reflect on these contingencies through the lens of digital product design, but the reflections I make apply to the entire domain of design (when I say “design,” I also mean many other trades, crafts, specializations, and domains of knowledge). But first, we’ll take a brief journey through the present state of the Internet.

Ted Nelson, a pioneering information technologist and philosopher who helped develop the directionality and ideological foundation of the early Internet, once wrote that “everything is deeply intertwingled.” Nelson continues, tearing down the notion of “subjects of study”:

“In an important sense there are no ‘subjects’ at all; there is only all knowledge, since the cross-connections among the myriad topics of this world simply cannot be divided up neatly.”

This notion of the intersectionality of knowledge domains led Nelson to invent the concept of hypertext, which is the foundation of the Internet as we know it today: an entangled mass of documents that link to each other using hyperlinks in order to form a network of knowledge, and ultimately, a network of peers, of real people.

Today, the Internet is broken. This is because of the planetary-scale centralization of power, resources, and attention into just a few repositories that lie in the hands of global sovereign corporations like Facebook, Google, Twitter, and Amazon. A new Internet is needed, and calls for this new Internet have been answered by projects like the InterPlanetary File System and the DAT Protocol — projects that aim to decentralize and dis-intermediate the web, reclaiming information, power, and attention from the hands of the central Internet powers.

The “intertwingularity” or entanglement of information in the world has been denied and slaughtered by the global Internet powers, which collect that information and force it into arbitrarily constructed ontologies, or structures. Accordingly, the interfaces through which we access and manipulate information have become centralized and turned into objects for the generation of capital — in short, interfaces and digital ontologies today exist not for the user’s well-being and the freedom of information, but for the accruement of dollars. Additionally, these interfaces obscure the inherent materiality of the Web: the mass of roots supporting it that consists of real people, submarine cables and fiber optics, rare-earth metals, plastics, and more elusive material activities like labor, resource extraction, server maintenance, and energy usage. This is unacceptable: it is an abomination to the technology and ideology invented by Ted Nelson and Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web.

The alternative, the horizon of hope, lies in sustainability.

Sustainability acknowledges inherently the intertwingularity of systems, things, people, information, and ideas. More than just “being green,” which is a shallow interpretation of sustainability at best, sustainability is an endlessly intertwingled set of actions and ideologies that work together to form a sustainable existence. Even more than that, sustainability is the way we respond to the collision of individual and collective actions with the material circumstances of the world. Sustainability is an activity, not a decision — it requires continuous action and inquiry. Sustainability is difficult to define, but I’ll give it a try: sustainability is the continuous act of questioning our contexts and acting in response to those questions in a way that maintains equilibrium in the network of forces that compose our contexts. Put more succinctly, sustainability is asking questions and answering those questions with actions oriented toward a balanced and enriched future. This is opposed to unsustainability, which can be defined as any activity that depletes resources and throws off the equilibrium of the contexts surrounding us.

Design is the ultimate substrate for sustainability. Design is the act of asking questions in order to solve problems within a set of constraints. All the way through, the design process involves questioning and acting, observing and responding. It is through this observation and response, which forms a dialectic whose synthesis is a design artifact, that design can become a model of sustainability.

The sustainable designer, and the sustainable individual in general, always considers a web of questions before acting on an intuitive or intellectual impulse. They question things in categories such as environmental sustainability, fiscal sustainability, and individual sustainability (physical and mental well-being).

This question-asking is a crucial step in the design process, because the questions asked work to form the boundaries of the solution space, or the domain of possible solutions to the problem, and in turn work to construct the form of the derived design artifact. If the questions asked include questions of sustainability, the derived design artifact will likely be more sustainable than otherwise.

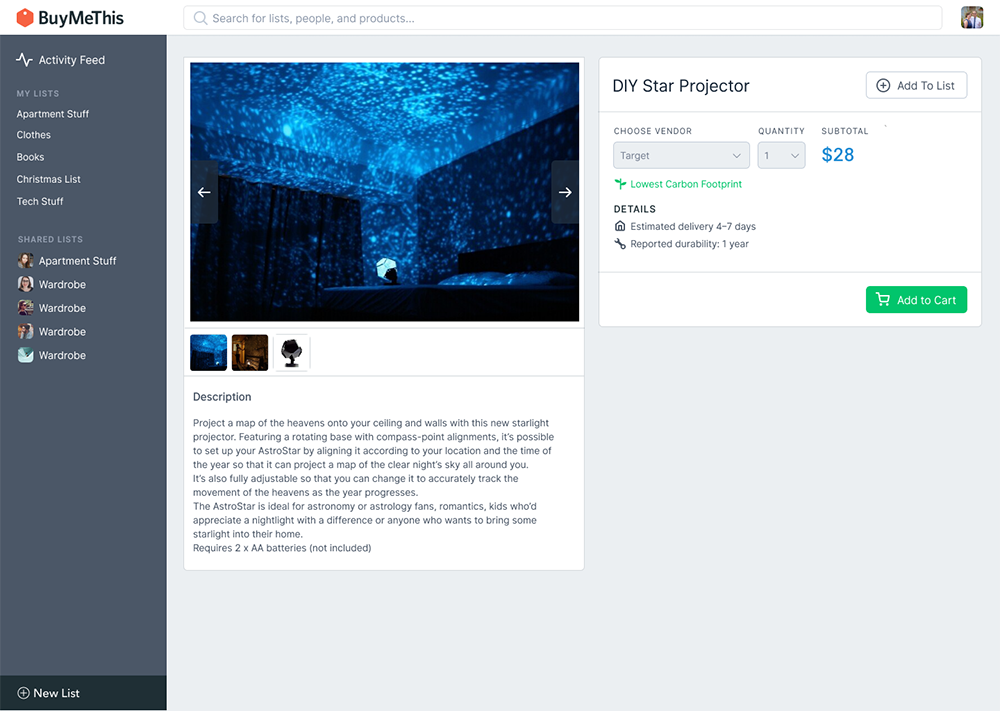

In the context of digital product design, sustainability is a tricky thing to define, and the questions we ask as product designers are difficult to think up. During Kristian Bjørnard’s Sustainable Design course, I worked on redesigning aspects of a product I had previously designed for a client, to make the project more sustainable. The product is a social wish list application called BuyMeThis, where users can add products they want to lists and share those lists with others (for example, it could be used for a birthday gift wishlist or a wedding registry). I began the redesign process by asking myself the following questions:

- What does sustainability mean in the context of this project?

- How can the product be more individually sustainable, more mentally sustainable for the user?

- How can the product be made more environmentally friendly through design decisions?

These questions led me to the final question that drove my investigation: How can the product encourage more responsible and sustainable consumption? This question led to a set of product/design statements and questions which were answered by a set of design decisions.

- How can I encourage users to consume the application’s content more slowly in order to respect their right to attention sustainability?

- How can I alter the functionality of the product in order to discourage unsustainable consumption?

- What behaviors am I trying to encourage or discourage in order to make sustainability a primary feature of the product?

These are the features I considered altering or introducing as a result of those questions:

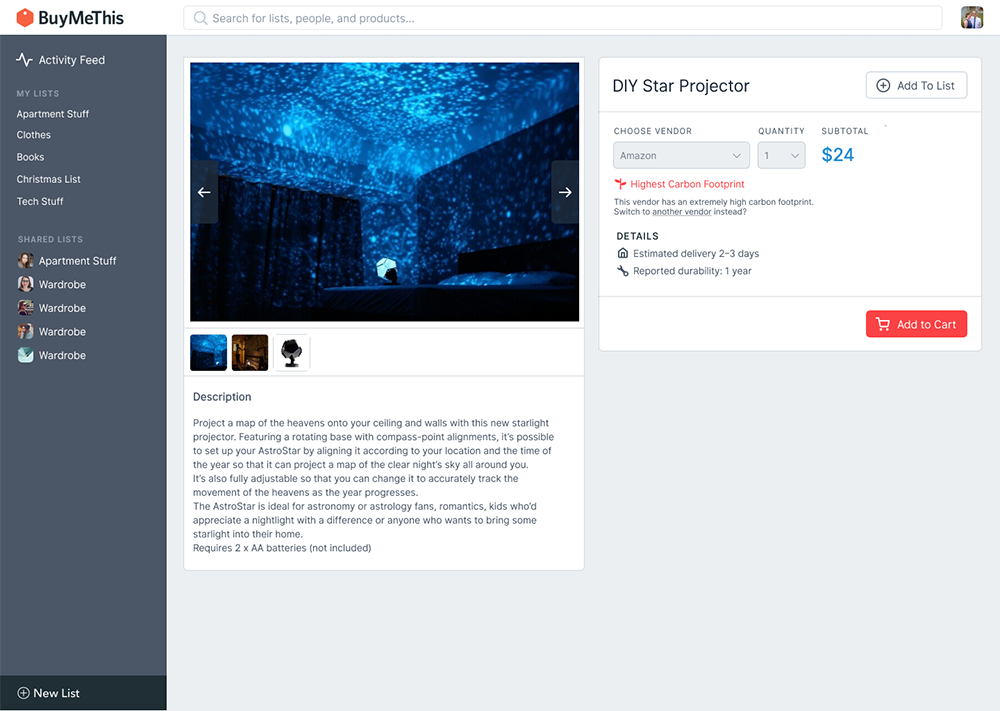

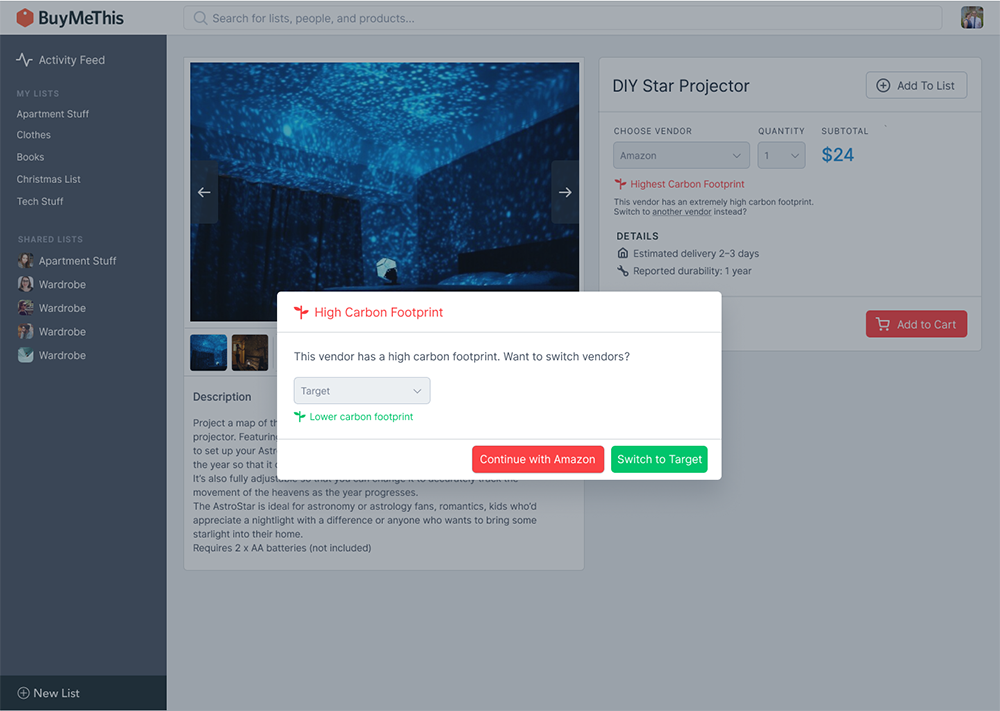

- A suite of small features to discourage buying products from vendors that are known to have a higher footprint than others.

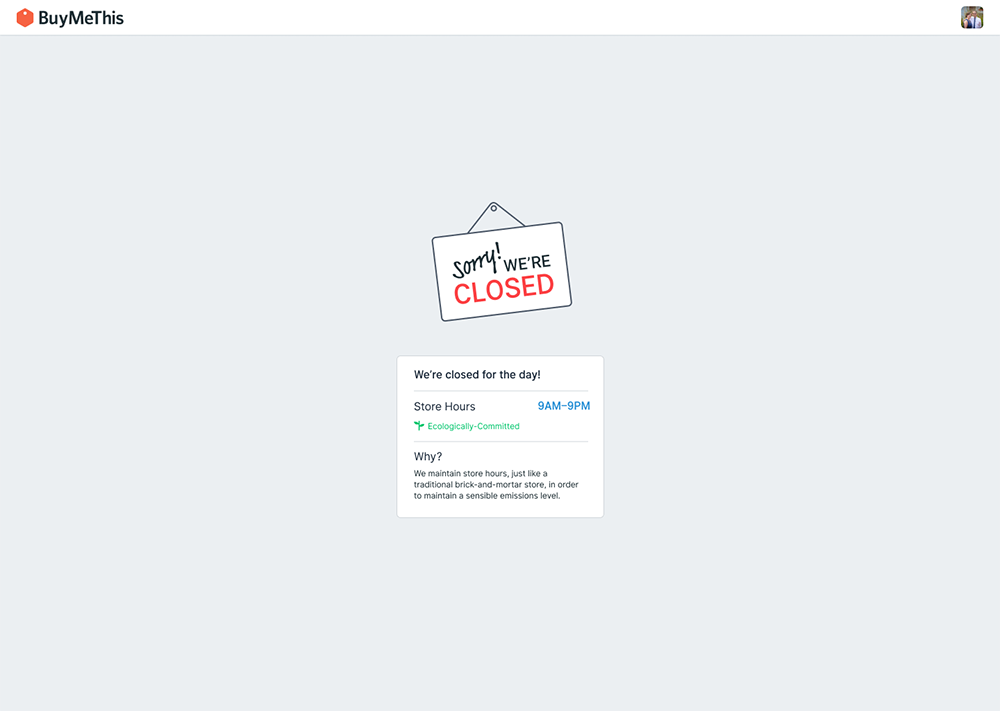

- Website/store hours, just like a real store, to discourage people from shopping 24/7 and consuming server energy at unnecessary times.

- A Product Durability metric exposed on product pages to help users choose products that they won’t have to throw away after a month of use.

- A product-level sustainability score, based on data gathered from third parties and on combined heuristics for determining “sustainability” (like cost, durability, materials used, and packaging method).

- A user-level sustainability score, based on the averaged sustainability scores of the products purchased by each user, that can be gamified and used to encourage users to buy more products that have higher sustainability scores in order to increase their individual score.

- User bonuses like discounts and access to additional features based on their sustainability scores.

Ultimately I only had time to focus on the first two of those features: vendor carbon footprints and website hours.

Website Hours

In our era of hyperconsumption and constant attention, we’re used to thinking of wesbites as something ethereal and always-on: for reasons I suspect most of us have never considered, we simply expect all websites to always be online and functioning. But this is an unsustainable ideal. For reference, around 2% of global carbon emmissions come from data centers powering the web, a market of which Amazon holds over 40%. Amazon’s AWS (Amazon Web Services) hosts around 5% of all websites, which includes major players like Netflix, which accounts for 30–40% of all Internet traffic, depending on your source; additionally, over 70% of all Internet traffic runs through Amazon’s northern Virginia data centers at some point in its path. Amazon’s AWS infrastructure is composed of around 50% renewable energy sources as of January 2018, but a large portion of that energy comes from nuclear power, which is non-renewable but low-emissions. 30% of Amazon’s energy usage comes from coal. Statistics on Amazon’s actual energy usage and emissions are difficult to find, but according to the 2018 IPCC report, the world’s combined energy usage in 2017 led to 36.2 gigatonnes of CO2 emissions (that’s 36,200,000,000 tons); if 2% of global emissions come from data centers, that means data centers worldwide emit around 724,000,000 tons of carbon per year; if Amazon owns 40% of the data center market and uses 50% renewable energy, a very conservative estimate of their yearly data center carbon emissions is around 144,800,000 metric tons per year. That’s a lot of fucking carbon, and this estimate is most likely wrong and far too low.

Giving websites store hours not only makes running a website more environmentally sustainable, it also forces users to consume content more slowly and at regular times, freeing up their attention and making internet usage more mentally sustainable.

Vendor Carbon Footprint Warnings

According to 350 Seattle and its sources, Amazon’s shipping operations in 2017 emitted at least 19.1 millions metric tons of CO2. This is equivalent to the average yearly energy usage of 2.9 million U.S. homes.

Some vendors have lower carbon footprints. For example, Target’s global shipping operations emitted only 2,982,884 metric tons of CO2 in 2017.

In an effort to encourage users to choose vendors and shipping options with the lowest emissions potential possible, I introduced several small features to discourage buying from vendors with high emissions rates. These features include:

- Introducing small amounts of friction into the user experience when users try to buy from high-emissions vendors;

- Warning users when buying from a high-emissions vendor, and reassuring users when buying from a low-emissions vendor;

- Introducing a carbon offset fee (which I called an “Eco-Fee”) for users who still choose high-emissions shipping methods.

- Making the default vendor and shipping method choices the lowest-emissions options so that users are more likely to choose them.

Sustainable Product Design

Ultimately, sustainable digital product design and software design is a relatively difficult concept to put into action. A major task of a product designer is to design an interface to a technology in order to make that technology accessible and understandable. But since these interfaces are so heavily abstracted from the underlying technologies, it becomes easy to forget that there is real materiality to our work. We’re not just pushing pixels and code, or just designing interfaces and icons; we’re also contributing to the global rare earth resource extraction apparatus, contributing to emissions by designing inefficient user flows that consume greater amounts of energy, and consuming labor and energy as a downstream effect of our work.

Product design’s extreme “intertwingularity” lends itself to an extreme amount of questions that need to be asked when designing a product responsibly and sustainably. Product designers need to be critical of their products and features, asking questions about their efficacy, sustainability, and usability. These questions can be hard to conjure up, because they often involve “unknown unknowns”, or the things we don’t know that we don’t know. Accessing these unknown unknowns requires research, patience, practice, and extended inquiry.

But these skills for accessing unknown unknowns and designing sustainably are not unique to product design. All designers have a duty to ask questions, to be relentlessly critical, and to perform thorough research. Sustainable design means designing things in such a way that they produce as little waste as possible, help to maintain equilibrium in the world, and push the world toward more equitable futures.

To bring this full circle, back to the broken Internet: asking questions and focusing on ubiquitus sustainability (that is, sustainability in all its facets: the environment, cost, the user’s attention, the designer’s energy, etc.) will lead us toward a better future where the software we use is not an imposition on us but a tool for our continued liberation and agency. Considerate, compassionate designers are what is needed in order to make this happen. To the reader, as you start your design and art practices, consider this advice as your point of departure: the world needs your criticality, intellect, curiosity, and compassion. Focus on growing those areas as much as possible during your time at art/design school. By the end of your time here, regardless of your approach and effort, you won’t know what art or design mean, or even how to practice art and design. But you will know something far more important: how to question, how to learn, and how to care.

Resources:

- Ethical OS — A toolkit and set of questions for designers to ask in order to ensure that their products are sustainably and ethically designed.

- Designing for Sustainability — Great article by UsTwo about sustainable product design.

- Sustainable UX — Another great article, this time from Shopify, that contains a good overview of things to consider when designing a product with sustainability in mind.

- Green Patterns — A pretty simple article that outlines a few tactics to consider when designing a sustainable product.

- Ambient Product Design — A project by software designer Alex Singh that explores ways of designing compassionate products, which is a critical aspect of digital sustainablity.

- Intertwingularity image sourced from http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/13/rosenberg.php.